Tungsten Carbide Manufacturing Process: From Powder to Sintering

ungsten carbide manufacturing explained: from powder preparation and mixing to forming, sintering, and finishing. Learn key processes, controls, and innovations.

Tungsten carbide, often referred to as “tungsten steel,” is a composite material made from high-hardness, high-melting-point metal carbides—such as tungsten carbide (WC)—and tough metallic binders like cobalt (Co) through powder metallurgy. It perfectly combines the hardness of ceramics with the toughness of metals, making it widely used in cutting tools, mining drill bits, molds, and wear-resistant components. Every step from powder preparation to final sintering directly affects the material’s ultimate performance.

Raw Material Preparation: Selection and Pre-Processing of Core Constituents

The performance of tungsten carbide is determined by its composition: refractory metal carbides—such as tungsten carbide (WC) or titanium carbide (TiC)—serve as the hard phase, while metals such as cobalt (Co) or nickel (Ni) act as the binder phase. The powder purity, particle size, and distribution directly determine the final product performance.

Low-price custom solutions. Our factory business includes designing, developing, and manufacturing powder metallurgy moulds, carbide parts, powder injection moulds, stamping toolings and precision mould parts.

WhatsApp: +86 186 3895 1317 Email: [email protected]

Key quality indicators include powder purity, particle size (commonly measured by Fisher Sub-Sieve Sizer), and particle-size distribution.

1. Selection of Primary Constituents

Hard Phase: Refractory Metal Carbides

The primary constituent is tungsten carbide (WC), which has a melting point of 2870°C and a hardness of HV1800–2200, forming the foundation of wear resistance in cemented carbide. Depending on performance requirements, additives may include TiC (improves red-hardness), TaC/NbC (grain refinement and impact resistance), or VC (grain-growth inhibitor). Typical addition amounts range from 1–10%.

Requirements: Carbon content controlled at 6.13%; impurities (O, Fe, Si) ≤0.1% to avoid sintering defects and incomplete densification.

Binder Phase: Transition Metals

Cobalt (Co) is the mainstream binder due to its excellent wettability with WC (wetting angle ≤10°), enabling strong bonding through liquid-phase sintering. Alternative binders include nickel (Ni) and Ni-Co alloys (improved corrosion resistance). Typical binder content ranges from 3–20%—higher Co yields greater toughness but lower hardness.

Requirements: Purity ≥99.5%; oxygen content ≤0.05% to avoid oxide inclusions.

2. Raw Material Pre-Treatment

Dewatering & Impurity Removal: Raw powders are vacuum-dried at 120–150°C for 2–4 hours. When oxygen content exceeds standards, powders must be reduced in a hydrogen atmosphere at 800–1000°C for 1–2 hours. Reduced Co powder shows higher activity, and reduced WC removes surface WO₃.

Particle-Size Screening: Powders are screened through 200–400 mesh sieves to remove agglomerates and ensure uniform initial particle size. Typical size ranges: WC powder 0.2–5 μm; Co powder 1–3 μm.

Powder Preparation: Synthesis and Control of the Hard Phase

The performance of cemented carbide is strongly influenced by the particle size and morphology of WC powder. Industrial WC powder is mainly produced through the “tungsten powder carburization process,” outlined as follows:

1. Tungsten Powder Production (Raw Tungsten Source)

Ammonium paratungstate (APT, (NH₄)₁₀W₁₂O₄₁·xH₂O) or tungsten trioxide (WO₃) is used as the precursor and reduced in two stages:

Step 1: WO₃ → WO₂ at 500–700°C in a hydrogen atmosphere

Step 2: WO₂ → W (tungsten powder) at 800–1000°C

Key parameters include temperature gradients (≈50°C/h) and H₂ flow rate (1–2 L/min), resulting in tungsten powder with particle sizes of 1–5 μm—critical to the final WC size.

2. Carburization Reaction (WC Powder Synthesis)

Tungsten powder and carbon black (≥99% purity, ≤0.1 μm) are mixed at the stoichiometric ratio W:C = 93.87:6.13 and carburized in a graphite furnace.

Low-temperature stage (800–1200°C): W₂C forms as an intermediate phase.

High-temperature stage (1400–1600°C): W₂C reacts with carbon to form WC.

Process control: inert/vacuum environment; 2–4 hour hold; 0.1–0.3% excess carbon added to compensate for carbon loss.

The final WC powder is a gray hexagonal crystal with particle sizes 0.2–5 μm.

3. Powder Refinement (Optional: Ultrafine/Nanostructured WC)

For high-hardness and high-wear-resistance applications, ultrafine (≤0.5 μm) or nano (≤100 nm) WC powder is used. Common methods include:

- Spray-drying + reduction–carburization

- Plasma processing (5000–10,000°C, rapid carburization)

Due to the agglomeration tendency of ultrafine powders, dispersants such as PEG are required during preparation.

Mixing and Granulation: Ensuring Uniformity and Formability

The purpose of mixing is to thoroughly and uniformly combine the tungsten carbide powder, cobalt powder, and any additional carbides such as TiC or TaC. Granulation improves powder flowability to meet the requirements of subsequent forming processes.

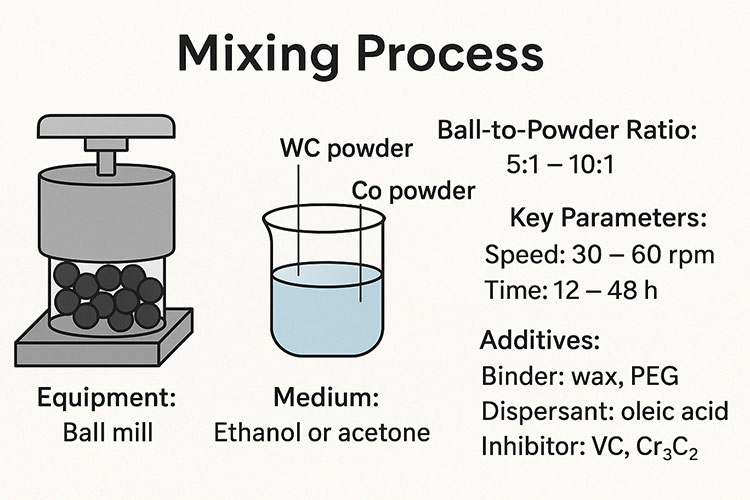

Tungsten carbide powder and cobalt powder mixing process illustration

1. Mixing Process (Primarily Wet Milling)

Equipment: Ball mills (rolling or planetary type) and attrition mills use impact and shear forces between milling balls to achieve mixing and particle refinement.

Medium: Absolute ethanol or acetone is commonly used to prevent powder oxidation. The solid–liquid ratio typically ranges from 1:1.2 to 1:1.5.

Ball-to-powder ratio: WC-Co milling balls to powder at 5:1–10:1 (ball size 3–10 mm depending on powder particle size).

Key parameters:

- Rotational speed: 30–60 rpm (rolling ball mill), 150–300 rpm (planetary mill)

- Milling time: 12–48 hours; uniformity verified via EDS analysis (Co distribution standard deviation ≤5%)

- Contamination control: WC-Co milling jars and balls to avoid iron contamination

Additives:

- Forming agents: paraffin (2–5%), PEG (3–8%) to improve green compact strength

- Dispersants: oleic acid (0.1–0.3%) to prevent agglomeration

- Grain-growth inhibitors: VC (0.2–0.5%), Cr₃C₂ (0.5–1%) to control WC grain growth during sintering

2. Drying and Granulation

Drying: The slurry is dried using rotary evaporation (60–80°C, −0.08 MPa vacuum) or spray drying (inlet 180–220°C, outlet 80–100°C) to remove solvents and produce dry powder.

Granulation: The dried powder is sieved through 20–60 mesh screens to break soft agglomerates and produce free-flowing granules.

Target properties:

- Loose bulk density: 1.5–2.5 g/cm³

- Flowability: ≤30 s per 50 g

- Satisfies press-forming requirements for uniform die filling

Forming: From Powder Granules to Green Compacts

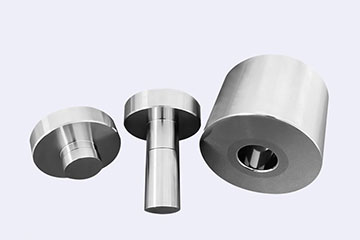

The goal of forming is to compress loose powder into a shaped compact (green body) with sufficient strength for handling and sintering. Common forming methods include pressing, injection molding, and extrusion, selected according to product complexity.

1. Pressing (Suitable for Simple Shapes: Inserts, Hammer Tips)

Molds: Carbide or steel dies with ±0.02 mm accuracy. Cavity surfaces are coated with mold-release agents such as zinc stearate.

Pressing Methods:

- Cold pressing: Performed at room temperature using a hydraulic press at 150–300 MPa with a 10–30 second dwell. Green density: 2.8–3.5 g/cm³ (55–65% relative density).

- Double-action pressing: Upper and lower punches press simultaneously to minimize density gradients and improve compact uniformity.

- Cold isostatic pressing (CIP): Powder is sealed in an elastic mold and subjected to uniform hydrostatic pressure (200–400 MPa). Green bodies achieve better density uniformity (60–70% relative density).

Key control points:

- Powder flowability ≥ 25 g/50 s to ensure uniform die filling

- Slow ejection speed ≤ 5 mm/s to prevent green-body cracking

- Avoid excessive pressure that may cause lamination or cracking

2. Injection Molding (For Complex Shapes: Special Cutting Tools, Precision Parts)

Feedstock preparation: The mixed powder is combined with binders (wax–PEG systems or polyolefins), typically 60–70% by volume. The mixture is compounded at 150–200°C and pelletized.

Injection: Feedstock is heated to 160–220°C and injected into molds under 50–150 MPa pressure. After 10–20 seconds of holding and cooling, the green part is ejected.

Debinding Process

Debinding removes binders to prevent pore formation during sintering.

- Solvent debinding: Parts are immersed in heptane or ethanol for 2–8 hours to dissolve PEG or other soluble binders.

- Thermal debinding: Performed in a nitrogen atmosphere at 200–600°C to remove waxes and high-molecular-weight binders. Green density after debinding: ≥50% relative density.

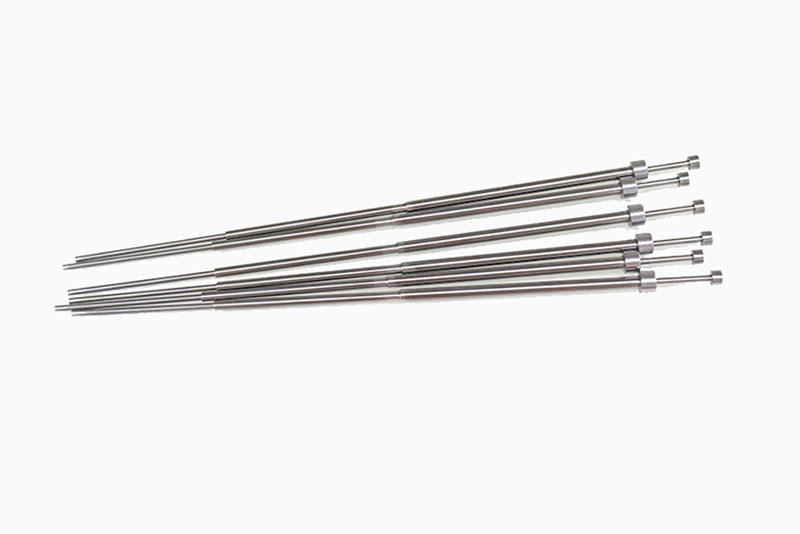

3. Extrusion (For Rods and Tubes)

Feedstock: Powder mixed with binders such as dextrin or carboxymethyl cellulose to create a plastic mass.

Extrusion: The material is extruded through dies at 50–100°C under 50–150 MPa to produce long rods or tubes, which are later cut to length.

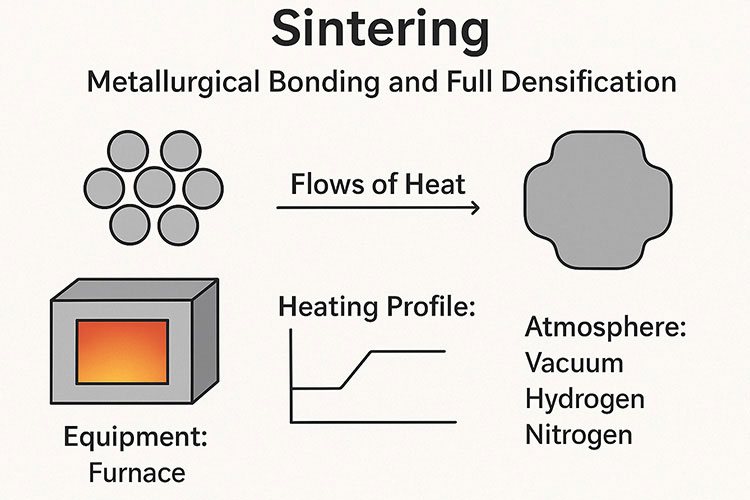

Sintering: Achieving Metallurgical Bonding and Full Densification

Sintering is the core stage of tungsten carbide production. Through high-temperature treatment, powder particles bond, diffuse, and densify to form a final product with the required microstructure and mechanical properties. Industrial production mainly adopts vacuum liquid-phase sintering.

Tungsten carbide sintering process illustration

1. Pre-Sintering Treatment (Debinding and Pre-Sintering)

Debinding: If forming agents are present, they must be removed during the early heating stage. Under vacuum at 200–600°C, the temperature is increased slowly (5–10°C/min) and held for 1–2 hours. Residual binder must be ≤0.1%.

Pre-sintering (800–1000°C): The goals are:

- Remove adsorbed gases (O₂, H₂O) from powder surfaces

- Allow initial diffusion within the binder phase to strengthen the compact

- Eliminate trace impurities such as sulfur and phosphorus

2. Sintering Stage (Four-Step Vacuum Liquid-Phase Sintering)

Sintering temperatures typically range from 1380–1500°C, 50–100°C above the binder’s melting point. Vacuum level must be ≥10⁻³ Pa to prevent oxidation and decarburization.

Stage 1: Low-Temperature Heating (Room Temperature → 1200°C)

Physical changes: Residual gases escape; binder decomposes; powder particles begin slight bonding through van der Waals forces.

Control: Heating rate 5–10°C/min to avoid cracking from rapid gas release.

Stage 2: Solid-State Sintering (1200°C → Binder Melting Point)

Chemical and physical changes:

- Cobalt begins diffusing

- WC particles develop neck growth between particles

- Relative density rises to 70–80%

- Pore volume decreases

Stage 3: Liquid-Phase Sintering (Binder Melting Point → Peak Temperature)

Binder melting: Co becomes fully liquid and fills the gaps between WC particles. Liquid-phase percentage ≈ 0.85 × Co content due to partial formation of WC–Co solid solution.

Key mechanisms:

- Wetting & capillary action: Liquid Co wets WC (wetting angle ≈ 0°), pulling particles together and driving densification.

- Dissolution–precipitation: WC partially dissolves into liquid Co and re-precipitates, creating metallurgical bonding.

- Rapid densification: Final relative density ≥95%; porosity ≤2%.

Stage 4: Holding and Cooling (Peak Temperature → Room Temperature)

Holding: 1–2 hours at 1380–1500°C to stabilize microstructure; WC grain size is controlled to 0.5–5 µm.

Cooling: Furnace cooling at 5–10°C/min (or oil cooling when required). Excessively fast cooling may cause thermal cracking. As Co solidifies, WC particles become firmly bonded.

3. Special Sintering Technologies (For High-Performance Alloys)

Low-Pressure Sintering (LPS)

During peak sintering, argon pressure of 0.5–5 MPa is applied to suppress WC decarburization (2WC → W₂C + C). Final density can reach ≥99.8%.

Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS)

Pulsed current generates rapid Joule heating (100–200°C/min). Sintering occurs at 800–1200°C under 50–100 MPa within 5–30 minutes.

Advantages: Produces ultrafine grain (≤0.5 μm) carbide with 10–15% higher hardness.

Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP)

Post-sintering compacts are processed at 1200–1400°C under 100–200 MPa of argon.

Effect: Eliminates residual pores; densification approaches 100%. Essential for high-end cutting tools.

Post-Sintering Processes: Enhancing Precision and Performance

After sintering, tungsten carbide components require a series of finishing and inspection procedures to ensure dimensional accuracy, structural integrity, and surface quality that meet application requirements.

1. Cleaning and Inspection

Surface cleaning: Oxide layers and surface residues formed during sintering are removed through sandblasting or light grinding.

Dimensional inspection: Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs) are used to verify critical dimensions and tolerances.

Microstructure analysis: Metallographic examination evaluates:

- WC grain size distribution

- Binder (Co) phase uniformity

- Pore content and morphology

Mechanical testing: Typical tests include:

- Hardness (HRA or HV)

- Fracture toughness (KIC)

- Transverse rupture strength (TRS)

2. Precision Finishing (As Required)

Grinding: Diamond grinding wheels are used to achieve the required surface roughness and geometric accuracy. Tungsten carbide’s high hardness makes diamond abrasives essential.

Edge preparation: Honing or edge-rounding removes micro-chipping and burrs, improving tool life and cutting stability.

Coating: PVD (Physical Vapor Deposition) or CVD (Chemical Vapor Deposition) coatings—such as TiN, AlTiN, TiCN, or DLC—are applied to enhance wear resistance, oxidation resistance, and cutting performance.

Key Process Controls and Common Troubleshooting

The performance of tungsten carbide is directly determined by powder quality, mixing uniformity, sintering densification, and microstructure control. Strict process control is essential to ensure stable performance and prevent defects.

1. Key Process Control Points

- Powder Purity: Oxygen content ≤0.1%, iron content ≤0.05% to prevent oxide inclusion and contamination.

- Mixing Uniformity: Cobalt distribution standard deviation ≤5% (verified through EDS mapping).

- Sintering Densification: Final density ≥99.5%, porosity ≤0.5% for high-performance grades.

- Microstructure Control: WC grain size must remain uniform (coefficient of variation ≤20%), with no abnormal grains ≥10 μm.

2. Common Problems and Solutions

Pore Formation (Excessive Porosity)

- Increase sintering temperature or prolong holding time

- Use low-pressure sintering or post-sintering HIP

- Ensure adequate binder content and mixing uniformity

Grain Coarsening

- Add grain-growth inhibitors such as VC or Cr₃C₂

- Reduce sintering temperature

- Shorten sintering holding time

Decarburization or Carburization

- Maintain proper vacuum level during sintering

- Adjust WC powder carbon content before mixing

- Add TaC/NbC to stabilize carbon balance

Cracking and Deformation

- Optimize pressing parameters to ensure uniform compaction

- Reduce internal stress with controlled cooling rates

- Use isostatic pressing to eliminate density gradients

Process Optimization and Innovations

Traditional WC-Co cemented carbide manufacturing involves multiple high-temperature steps—carburization and sintering—which are energy-intensive and time-consuming. Recent technological developments aim to simplify processing, shorten cycles, and improve microstructure control.

1. In-Situ Carburization and Rapid Sintering

This method uses tungsten powder, cobalt powder, carbon black, and organic carbon sources as raw materials. Carburization and sintering are completed simultaneously within a spark plasma sintering (SPS) system.

Key findings:

- The best phase composition (pure WC + Co) occurs when carbon content is 1.2× the theoretical value.

- At 1250°C, WC grains are uniform with no abnormal grain growth.

- Optimizing pressure profiles significantly reduces porosity and increases densification.

2. Plasma-Assisted High-Energy Ball Milling

Dielectric barrier discharge plasma is used to enhance high-energy ball milling efficiency, enabling effective refinement and activation of W–C–Co powders within 1–3 hours.

Advantages:

- Significantly shorter milling time

- Activated powders can be directly sintered around 1390°C

- Realizes “one-step carburization + sintering”

- Eliminates the need for two separate high-temperature processes

3. Microwave Reaction Sintering

Using W powder, Co powder, and carbon black as raw materials, microwave heating enables both carburization and densification.

Key observations:

- When temperature exceeds 1100°C, W is fully carburized into WC

- At 1300°C, the alloy achieves good densification

- Microwave heating provides rapid, uniform internal heating, leading to finer microstructures

Conclusion

The manufacturing of tungsten carbide is a highly precise and systematic engineering process—from powder preparation to mixing, forming, sintering, and final finishing. Each stage directly influences the material’s hardness, toughness, and wear resistance. With ongoing advancements in ultrafine powder production, rapid sintering technologies such as SPS, and innovative one-step carburization methods, tungsten carbide continues to evolve toward ultrafine grains, higher density, and multifunctional composite structures.

In the future, these improved materials and processes will play an increasingly important role in aerospace, high-end manufacturing, precision tooling, and other advanced industrial fields.

Connect with us